EU Candidate Rating: Can Ukraine Catch Up with Western Balkans? Analysing EU Commission Report-2023

Last week, the European Commission released an EU enlargement report that many considered historic. Brussels has acknowledged for the first time that Ukraine has "matured" enough to start accession negotiations, meaning that it sufficiently meets the Copenhagen criteria for EU membership.

Of course, the most crucial part is still ahead.

First, Ukraine needs to get the green light at the EU summit in December, overcoming resistance from Hungary. Then, lengthy accession negotiations will begin, meaning that Ukraine will have to meet all the requirements for EU member states.

The government says Ukraine is at a high level of readiness for accession and has pledged to complete the negotiations within two years. But is that realistic?

It is important to understand that several other countries are heading towards EU accession at the same time as Ukraine. Ukraine needs to "jump" into the next wave of enlargement because there might be a pause afterwards. Therefore, Ukraine needs to catch up with the leading candidates. Who are they? Is it true that Ukraine should be measuring its progress based on their results?

The answer to all these questions lies in the so-called "enlargement package" – a set of reports over a thousand pages long that the European Commission released along with its recommendation on opening negotiations with Ukraine. European Pravda has analysed these documents and prepared a brief summary for you.

Unfortunately, Ukraine is not a front runner among the candidate countries.

Its strength and potential success lie in the speed of reforms, which has been decent, but still not the best. Moldova is the leader in this field.

Ukraine's speed currently does not give much hope that the negotiations will be completed within two years. It needs to move ten times faster if it is to achieve membership in the foreseeable future.

At the moment, Ukraine and Moldova are behind all the other countries currently negotiating or about to start negotiations with the EU – Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Their levels are currently approximately the same. Albania remains the only Balkan country that continues to progress towards membership.

In contrast, Türkiye’s relationship with the West has deteriorated disastrously, and it continues to drift further away from Europe year upon year. Although Türkiye is the most integrated with the EU economically and it has excellent average ratings, in reality, it has lost its chance of accession.

How to assess the "level of Europeanisation"?

It's not uncommon to hear Ukrainian officials and politicians saying that Ukraine, even within the framework of the Association Agreement, has completed most of the tasks necessary for EU accession. This, of course, is not the case. The amount of work that lies ahead of Ukraine during accession negotiations is incomparably greater than the amount it has accomplished during association. Moreover, along the path to membership, the European Union monitors the extent to which each decision made for accession negotiations complies with EU law. That was not the case with association.

However, there is still a lot of confusion in Ukraine.

Sometimes the media also gives the public unwarranted hope. For example, in early 2023, Ukrainian media outlets were arguing in their headlines: some claimed that Ukraine had already met over 70% of the conditions for EU accession, while others were claiming 72% compliance with the Association Agreement. The second option is, of course, the correct one. Regarding the Association Agreement, experts consider this government assessment to be overly optimistic.

But how is Ukraine doing in meeting the accession conditions?

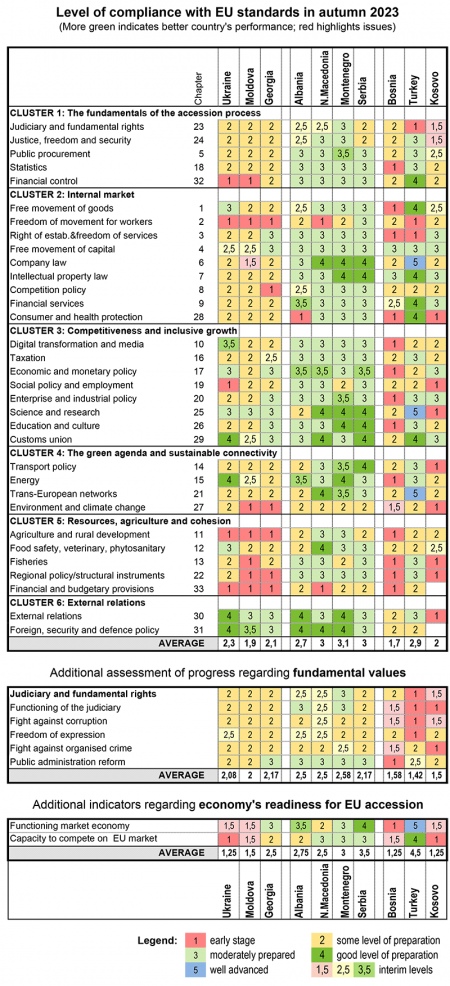

To answer this question, we have created a table presenting the official EU assessment.

This calculation is done each quarter by the European Commission. It evaluates all of the countries that have candidate or potential candidate status for EU membership using a uniform methodology.

In 2023, Ukraine entered the regular report for the first time.

In the "enlargement basket", there are 10 states that we have divided into three groups with similar assessments.

The first group consists of the three "Eastern Partnership" states: Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

The second group is the Western Balkan states. The EU is officially conducting accession negotiations with Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Albania.

The third group comprises problematic states. This includes Türkiye, with which the EU officially halted negotiations several years ago due to undemocratic processes in the country. Bosnia has such an ineffective post-war governance system that many consider it a failed state.

Kosovo’s independence is still not recognised by five EU states. In Ukraine, Serbia is often included in the "problematic" category due to its pro-Russian stance, which diminishes its chances of joining the EU. However, this is a political issue, and technically Serbia has decent indicators.

What do these figures mean?

First and foremost, the European Commission evaluates compliance with EU law in 33 sectors, according to the chapters of the agreement on the accession of new states to the EU. These chapters and their requirements are standard for all candidates and form the basis for accession negotiations.

In the European Commission's report, there are five levels of compatibility between the state and EU law:

- early stage;

- some level of preparation;

- moderately prepared;

- good level;

- well advanced (at this level, negotiations on the chapter can be closed).

We have assessed these levels and given scores from 1 to 5 respectively (with a step of 0.5 points where the EC report contains an assessment "between levels"), and have also calculated the average score for each state.

However, technical convergence with EU law alone is insufficient for EU accession.

The level of a candidate's adherence to the EU's basic values is no less important. It is not by chance that Chapter 23 on the fundamental values is opened first and closed last during negotiations with candidates. Throughout the entire negotiation process, the EU monitors candidate countries’ compliance with these issues and seeks to influence them. If this is unsuccessful, negotiations are suspended, as happened with Türkiye in the past.

Therefore, we have added a separate block for the values that are fundamentally important to the EU. This is probably the best indicator of who has a chance of joining the EU and who does not.

The final block is the EU's assessment of the country's readiness to integrate into the EU market.

Ukraine and Moldova – a fast-moving group of "average performers"?

The table above clearly shows that there are no grounds for saying that Ukraine is a front runner among the states aspiring to join the EU. With an average score of 2.27, we lag significantly behind all the Western Balkan candidates. The gap with Albania (average score 2.74) is almost half a point, and it’s even bigger with the other candidates.

All the Balkan states, including Serbia, which is trailing behind the most, are at least at the same level as us in terms of the additional indicators related to fundamental EU values. Regarding market readiness for accession, Ukraine is an outlier among all the enlargement states, even those in the "problematic" group.

To join the EU, Ukraine must rapidly catch up with the Balkan candidates.

The same applies to Moldova, which is politically linked to Ukraine regarding EU membership.

Currently, both countries have earned an "average performer" grade: Moldova has an average score of 1.92, while Ukraine’s is 2.27.

But there is good news. Ukraine and Moldova are the leaders when it comes to progress, even though their speed is still insufficient.

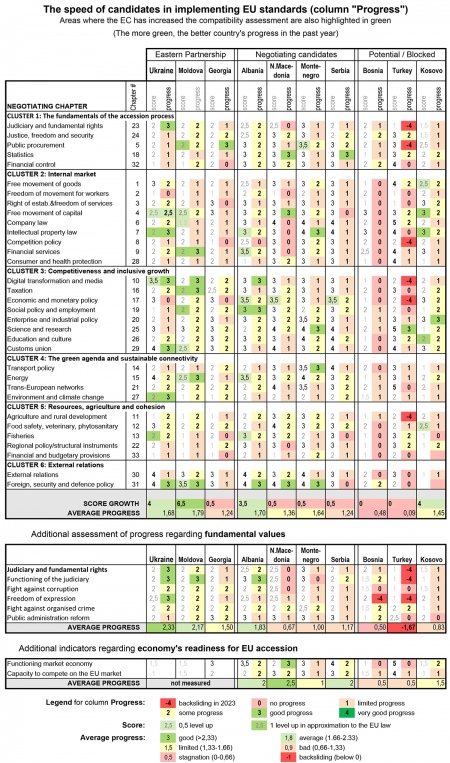

Our next table is more complex, but it is more critical.

The previous table determined the current state of integration, but this one enables us to conclude whether a candidate country such as Ukraine is capable of achieving the final result – whether it is moving towards membership and how quickly.

The columns entitled "Actions in 2023", in which all the cells are colour-coded, provide an assessment of each candidate’s progress over the past period. These comprise data and assessments from the European Commission which we have converted into scores as follows:

- 4 points – very good progress (no state received this assessment this year),

- 3 points – good progress,

- 2 points – some progress,

- 1 point – limited progress,

- 0 points – no progress,

- 4 points – rollback of reforms.

We have deliberately assigned a high negative score to those states that have demonstrated a rollback in reforms, because if a country is not just stagnating but moving away from the EU, this is an indicator of systemic problems. Türkiye and Bosnia are currently experiencing such setbacks.

This parameter is about the intensity and quantity of pro-European reforms that a country is undertaking.

The "Level" columns provide the indicator from the previous table, and some cells are also colour-coded. These are the areas in which the country has moved up one level of adaptation to EU law in a year (by half a point or a full point), meaning it is getting closer to closing accession negotiations in that area. Essentially, this parameter indicates the choice of the most effective path of reforms, when the country addresses precisely what is needed to improve the EU assessment.

Here, Ukraine's indicators seem excellent. But only at first glance.

Despite the war, which is hampering systemic reforms, Ukraine has firmly secured its position in the top three, with a significant lead over other candidate states.

Yes, over the past period, it has managed to improve the EU assessment in five areas. Ukraine has moved up one level in three areas and half a level in two. And everything is good in terms of the intensity of reform – we are in third place.

But the leader among all 10 enlargement countries is Moldova.

Although Chişinău is considered an "average performer" in terms of EU integration, according to the EU assessment it has increased its score in nine chapters over the past year (a total of 6.5 points, the record among all candidates). No doubt the fact that the Moldovan government has a clear and effective majority in parliament and has no problem gathering votes for complex reforms played a role here.

Georgia, however, has clearly failed. This is not surprising given that the government's policy in Tbilisi is becoming increasingly pro-Russian. For this reason, Georgia has not improved its level of compliance with EU law (only 0.5 points in total) and has a poor reform intensity indicator ("limited progress" in most areas).

But are the results of Ukraine and Moldova sufficient to claim success? Definitely not!

Their indicators seem "successful" only because most of the other candidates (not only Georgia, but also the Balkan states) are stagnating and implementing no reforms at all. Meanwhile, even at Moldova's pace of reform (+6.5 points per year), it would still take about 15 years to fully meet the EU’s requirements (5 points for each chapter and closing negotiations on them).

Needless to say, these are absolutely unacceptable estimations.

So next year, without even waiting for the formal opening of negotiations, Ukraine needs to increase the pace of reforms tenfold, as this is the only way to achieve the current level of Euro-integration reached by the Western Balkans. And when we say "tenfold", that means literally, not figuratively. But is this realistic?

The three front runners, with Albania in the lead

First of all, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kosovo and Türkiye are currently out of the running.

Türkiye deserves special attention as it has no realistic chance of returning to the enlargement package even in the long term. Moreover, Türkiye has been steadily moving away from the EU for several years now.

Türkiye's indicators relating to fundamental EU rules and values are also deep in the red zone, which fuels the arguments of those who say that it's time Türkiye abandoned its ideas about European integration. Russian propaganda has long liked to use this country as an example to convince Ukrainians that they are not welcome in the EU, saying, "Look at Türkiye!" But it’s a false argument. Türkiye's stagnation and estrangement from the EU are solely the fault of the Turkish government and society.

Bosnia is not a good example either. It has a special federalised system. The anti-Western Republic of Srpska is capable of blocking the country's movement westward and its development in general. The European Commission’s assessment vividly confirms this. During the era of the Minsk Agreements, Russia tried to impose the Bosnian model on Kyiv. Ukraine did not agree to this.

Moreover, there is no reason to compare Ukraine with partially recognised Kosovo. It seems its European integration is blocked until Kosovo and Serbia agree on a peaceful separation.

The quartet of Balkan states that remain have a similar level of European integration according to the EC assessment. However, Serbia's ratings for compliance with fundamental EU values are significantly lower than the others’. And most importantly, Belgrade officially adheres to a policy of cooperation with Russia rather than Brussels on international policy and security issues. This is blocking its path to membership.

Ukraine's competitors for EU membership are Montenegro, North Macedonia and Albania. The latter is slightly lagging behind in terms of its integration level (2.7 points compared with 3-3.1). However, in terms of enthusiasm, the Albanians are clear leaders. They are the only state in this stagnant region that continues to actively implement reforms. This is a country that Ukraine should pay particular attention to.

In general, Kyiv should aim to overtake all the other candidate countries and become a leader in the process of convergence with the EU. Ukraine needs to be more realistic in assessing its capabilities. When claims are made about Ukraine’s ability to complete membership negotiations in two years, these words must be backed up by the actions of the Ukrainian government.

Sergiy Sydorenko

Editor, European Pravda