From "corruption" to newscast: what EU expects from Ukraine and how it assesses its readiness to join

On 30 October, the European Commission published its annual enlargement report, a comprehensive document assessing the situation in all candidate countries. Since last year, Ukraine has been included in the enlargement package, meaning the EU sees it as a future member state. Ukraine is covered in a separate 100-page document that audits the country’s readiness for EU accession across every sector and negotiation chapter, as well as the pace of its progress.

Since EU accession requires Ukraine to amend hundreds, if not thousands, of legislative norms, the European Commission uses this report to publicly outline the most urgent tasks that must be implemented.

This report also serves to commend candidate countries if they demonstrate significant progress in certain areas. There are positive points for Ukraine in some surprising areas.

It is no secret that both the West and Ukraine have a stereotype of Ukraine’s catastrophic levels of corruption, allegedly hindering its EU progress. However, Brussels sees the situation differently, highlighting Kyiv’s record success in combating corruption. The recent uncovering of numerous corruption cases is considered a positive step toward membership.

The European Commission has made it clear that it does not expect elections in Ukraine until martial law is lifted. The EC also defended the opposition, noting certain issues, and for the first time has publicly criticised the newscast.

The pace of Ukraine’s compliance with the EU is mixed. The report gives a lukewarm assessment of the volume of reforms over the past year but emphasises that right now, the focus is on screening speed and preparation for opening chapters, where the situation is quite positive. But Ukraine should also be prepared for new requirements coming from EU member states.

Good progress, zero change

Is Ukraine moving swiftly toward EU membership? And is it moving at all? The Ukrainian government, opposition, EU itself and individual member states answer these questions in very different ways.

To establish a common baseline in this assessment, the EU developed a bureaucratic tool to evaluate all candidate countries using a standardised methodology. Ukraine received this assessment for the first time last year, giving the EU much to consider and showing its actual standing compared to other candidates, especially Moldova and the Western Balkans.

The second full report on Ukraine, released this year, was intended to show how swiftly Ukraine is complying with the EU.

The indicators in this report do not provide much cause for optimism. The European Commission rated Ukraine’s reform pace at last year’s low level. On a scale from 0 to 4, it received 1.79 (last year, it was 1.68). In six out of 33 areas, Ukraine demonstrated "good progress," which is an average mark. However, it achieved no top score in the speed of reforms in any of the future EU negotiation chapters.

The result is predictable. Over the past year, Ukraine has not come any closer to meeting the standards expected of an EU member state. In one chapter only (Entrepreneurship and Industry), Brussels increased Ukraine’s readiness score by 0.5 points out of five.

It could take centuries to join the EU at this pace! One could be reassured by the fact that, according to the European Commission, Ukraine has shown no "backsliding." Not that comforting though.

One might think that this would be a wake-up call for Ukraine’s EU integration team. But not really.

All European Pravda’s sources in Kyiv and Brussels urge against drawing hasty conclusions, stressing that this pause, while unfortunate, is offset by other achievements.

"Right now, the report isn’t the main focus. We’re preparing for the opening of negotiation chapters, conducting screenings. And everything is going positively here," explained a European diplomat who shared insights on the internal workings of Ukraine-EU negotiations on condition of anonymity. "The primary focus is on negotiations, screening reports and the Ukraine Facility plan (lists reforms and conditions for granting Ukraine €50 billion in aid)," echoed a Ukrainian official.

The importance of screening and its positive progress is confirmed in the report itself. Another positive signal is that, in an official statement, the European Commission expressed its intention to open multiple negotiation clusters with Ukraine soon. This detail, though technical, represents a significant breakthrough for Brussels. It indicates that the EU is inclined toward accelerated negotiations with Ukraine.

However, if the current reform pace continues, this opportunity will not be fully used by Ukraine. The pace needs to increase significantly. Still, there are reasons for optimism in 2025.

Hungary no longer opposed

An important and unexpected success for Ukraine in this report was how Hungarian demands on national minority rights were addressed.

The EU Commissioner for Enlargement is Viktor Orbán's appointee, Olivér Várhelyi, who has a reputation for remaining aligned with Hungary’s government and has previously pushed for EU decisions that align with Orbán’s stance. The European Commission is set to change in December. Várhelyi will lose his post. It was concerning that this report, presented personally by Várhelyi, was published now.

However, the document’s language exceeded the boldest expectations.

The European Commission finally concluded that Ukraine’s reform of minority rights legislation last year, in response to EU and Hungary’s requirements, was sufficient. Hungary and its affiliates continued to criticise Ukraine, disputing that the recommendation was fully implemented.

Brussels has clearly stated that no further amendments to minority legislation are needed. The only requirement for Kyiv is to "continue implementing the revised legislation... in close cooperation with representatives of national minorities."

Furthermore, Brussels took an unprecedented step by indicating it would not wait for a Venice Commission ruling (lately, this authority has been issuing critical decisions regarding Ukraine). "We note that the Venice Commission had not updated its recommendations, the European Commission believed that Ukraine had taken the necessary measures," the report states. This stance sharply contradicts the recent position of Hungary’s leader, who continues to demand legislative amendments (see the article Orbán’s 11 demands).

In addition, Várhelyi not only agreed to these terms in the document but also refrained from mentioning minority issues at the press conference. It was as if he had changed his mind completely!

Despite the significance of this shift, it’s essential to remain aware: even if Hungary has temporarily eased pressure and lifted its blockade on Ukraine’s EU accession process, it doesn’t mean that the "minority issue" won’t resurface in the future.

Since decisions on opening clusters require unanimity from EU member states, Hungary retains real leverage to reintroduce its demands into the EU-Ukraine agenda in the future.

No election, no newscast

The EU is primarily a trade bloc, but when it comes to new members, the deciding and most challenging factors are not economic but rather political and value-based criteria. These criteria are pivotal in the EU’s enlargement report regarding Ukraine.

In areas like agriculture, transport or fisheries, compliance with membership criteria can be assessed fairly objectively, given the clear norms in EU law that must be adopted into national laws and implemented consistently with other EU states. But the political domain lacks such precision.

The EU does not have a single standard for arranging, for instance, a judicial system. Rules cannot simply be transferred from one country to another. Without high-quality justice, even the economic integration with the EU will falter, despite full compliance with technical standards.

Thus, the EU doesn’t hesitate to set political requirements for candidate countries, even if formally labeled as "recommendations."

Some of these may be open to debate, especially if the candidate country has an alternative, more effective way of upholding shared European values. But more often, these demands must simply be met.

The report on Ukraine brought several positive surprises. The European Commission has finally acknowledged certain issues, long known in Brussels but previously lacking the political will for official recognition. It also outright dismissed some misgivings about Ukraine voiced internationally.

This includes matters related to anti-corruption, which we’ll discuss further.

First and foremost, Brussels has repeatedly stressed that it does not expect Ukraine to hold elections until martial law is lifted.

This point is highlighted as the first item in the European Commission’s main conclusions regarding the state of democracy in Ukraine, stating that any recommendations on elections pertain to "preparing for post-war elections." The EC also reiterates that all parliamentary groups agreed to this approach. There should be "enough" time to announce the electoral process beforehand.

Ukraine is expected to make changes to the work of the current parliament until then. This expectation is one of the highlights of the political section of the EC report.

Brussels officials have finally decided to break their silence on long-known issues related to the rights and powers of the opposition. For now, however, this is conveyed in soft language, without direct accusations, such as the phrase, "the parliamentary opposition must be able to perform its function," found in the section on changes that are necessary for upholding democratic standards. Notably, similar remarks were absent in the 2023 report.

There are also more specific observations. Brussels claims to be aware of "cases of disproportionate travel restrictions on members of the parliamentary opposition that require proper response." European Pravda has also discussed this issue, noting that these restrictions have reached a level that is harming Ukraine’s image internationally (more on this in the article). The European Commission’s open criticism of the government’s actions suggests that the problem has reached a substantial scale.

In general, however, the EU’s view of Ukraine’s parliament’s work is quite positive, perhaps even more so than some members of the opposition in Ukraine would like.

UPDATED: However, parliament insists that this section of the report does not account for recent changes in Ukraine's parliament. First Deputy Speaker Oleksandr Korniienko emphasised that parliament has resumed holding "question hours" for the government during its sessions. "Several important steps have been taken to enhance parliamentary openness and government accountability, though, unfortunately, these are not mentioned in the report. We hope that future reports will reflect these changes," he stated in a comment to European Pravda after the article's publication.

Some existing restrictions are also considered acceptable given wartime conditions. For example, current parliamentary oversight is limited to meetings between ministers and pro-government group leaders. While this is suboptimal, the EU understands that it’s unlikely to change until martial law ends. In some specific areas (such as the work of the Accounting Chamber), Brussels expects Ukraine to strengthen parliamentary oversight immediately, without waiting for the end of the war.

However, the section on transparency in Ukraine’s parliament contains truly revolutionary ideas. While Ukrainian authorities often criticise opposition figures like Oleksiy Honcharenko and Yaroslav Zhelezniak for holding online broadcasts of parliamentary sessions, closed during martial law, the EC sees their actions as a positive example.

The critique of the newscast 24/7 was even more revolutionary.

This topic had long been a taboo in public statements by European officials. They were aware of it and raised it in every private meeting with media representatives since 2022 but avoided public criticism. That has now changed.

One of Brussels’ most critical observations concerns the state-funded newscast 24/7.

"In 2023, the Ukrainian government invested public funds into the TV marathon project. It should be reassessed whether this is the best platform for enabling a free exchange of views among Ukrainians," the document states. Separate criticism was directed at the parliamentary television channel Rada, which, despite its declared impartiality, ignores the opposition.

Most importantly, the EU included changes in the media landscape to the top priorities for Ukraine as a candidate country. Regarding television broadcasters, the document states that the EU expects Ukrainian authorities to "gradually restore a transparent, pluralistic, and independent media landscape," which would include allowing channels to broadcast independently from the newscast.

This marks a radical shift from the previous year when the EC’s recommendations called for a "post-war plan to restore a pluralistic media landscape." This year, the phrasing calls for immediate changes, without waiting for the war to end.

This illustrates how the West is beginning to scrutinise Kyiv’s references to martial law as justification for limiting rights. While this argument remains effective in some areas (such as elections), it is increasingly unpersuasive in others.

Another area where the EU does not consider the war a sufficient justification for government actions is the independence of local authorities. The EU cautions against expanding the practice of Kyiv establishing direct control over communities through military administrations, sidelining elected mayors. The European Commission advises that this tool should only be used in extreme cases.

Combating corruption: better than expected

When it comes to anti-corruption efforts in Ukraine, the EU’s assessment is much better than many anticipated. Recently, a consensus has emerged among EU officials closely involved with Ukrainian issues: a major challenge for Ukraine is the "absolutisation of corruption" among Western politicians and the myth that "Ukraine is the most corrupt state," which Ukraine specialists view as completely unfounded. And this narrative isn’t just coming from figures like Donald Trump or J.D. Vance.

"We even hear this view from ambassadors who have come to Ukraine, claiming that ‘over the past five years, the corruption [level] in Ukraine has only increased.’ We explain that this is absolutely not the case! There are more known cases, more incidents being uncovered. But this indicates not an increase in the corruption [level] but rather in the effectiveness of combating it!", a Western official explained passionately during a recent meeting with journalists, including those from European Pravda.

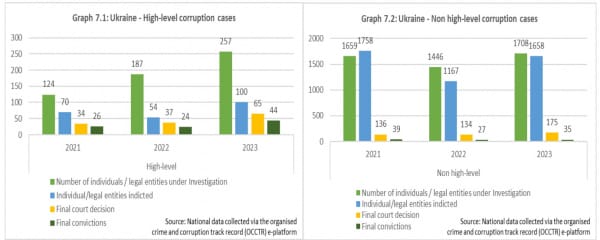

The European Commission, in its report, appears to aim at debunking this myth. While acknowledging that business in Ukraine "still feels the effects of corruption," the document emphasises that Brussels is quite satisfied with Ukraine’s progress in this area, especially in 2024. "Anti-corruption institutions continued their efforts in building a credible track-record of investigating and adjudicating high-level corruption cases and the overall number of indictments and judgments during the reporting period has reached an all-time high since the key anti-corruption institutions," the European Commission states, including graphs to support it.

The tasks set by the EU for Ukraine in this area, aside from general calls to continue fighting corruption and securing convictions, include the following: Ukraine must increase the number of judges for the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC); strengthen the capabilities of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) pertaining to forensic examinations and independent wiretapping; urgently finalise the deployment and complete operational use of the e-case management system for the anti-corruption agencies and the HACC, and see to it that the HACC has suitable permanent premises.

Tasks, but no deadlines

Overall, the 100-page report on Ukraine is a thorough and balanced document. There’s criticism of Ukraine, and it’s well-aimed. And there are positive signals where Kyiv’s efforts deserve support.

The wealth of detail illustrates that the European Commission has a strong understanding of Ukraine’s real problems rather than relying on stereotypes. The authors of the report highlight multiple times that a growing problem for business in Ukraine is the labour shortage. This is indeed a serious issue, and it’s something the European bureaucratic machine should consider already, possibly by developing programs to encourage refugees to return to post-war Ukraine.

However, there is also a drawback to the report due to its format.

Since EU enlargement is an open-ended process that depends on the candidate state’s efforts, the document contains no deadlines for implementing particular reforms. This is actually one of the reasons why Ukraine’s progress has slowed sharply over the past year.

This is a unique aspect of the Ukrainian government system.

In Ukraine, to launch the legislative process and achieve the approval of comprehensive reforms, it’s crucial to have a clear list of tasks and a pressing deadline.

This combination can work wonders in lawmaking, which Ukraine has seen multiple times, both in implementing the so-called "7 steps" and in fulfiling the "visa-free" action plan.

Over the past year, Ukraine has been in an interim period, working on the formal launch of the negotiation process but not yet starting substantive negotiations. Consequently, there was neither a list of priority reforms for accession nor deadlines.

However, this also provides grounds for cautious optimism regarding the acceleration of Ukraine over the next year or so when the opening of key chapters in the negotiation process finally becomes visible. Targeted plans will accompany these chapters. The government machine will have the opportunity to show that its desire to join the EU is more than just rhetoric.

And if the pace of implementing EU norms into Ukrainian law remains the same it was in the past year, there will be no reason to expect the country joining the EU within 10 years or ever.

The European Union, having declared its readiness to open several negotiation chapters with Ukraine in 2025, has made its move. Now it’s Ukraine’s turn.

Sergiy Sydorenko

European Pravda, Editor

Translated by Daria Meshcheriakova

Edited by Ivan Zhezhera