EU enlargement on hold? А wake-up call for Ukraine and other candidates in the new Commision report

The European Commission has published its Enlargement Package – a detailed report assessing each country with candidate or potential candidate status. It serves as an audit of European integration.

The scores achieved by Ukraine are not always inspiring. Officials in Brussels and Kyiv alike have pointed out that Ukraine has had unique challenges and priorities over the past year (read more in the article From "corruption" to newscast: what EU expects from Ukraine and how it assesses its readiness to join).

A slow pace of alignment is an issue for all the candidates –

from Moldova (which has some of the best results) to Türkiye, whose progress appears hopeless.

Meanwhile, Georgia has effectively abandoned its EU aspirations. Its policies are incompatible with a European future. The report reveals that Georgia’s problems run far deeper.

The Balkan states, too, have failed to initiate reforms at a sufficient pace.

The 2024 report raises the question of whether the candidate countries genuinely want EU membership. It also sends out a message to those states that truly want to jump on the European train while this historic window of opportunity is open: it's time to wake up and get started on the technical work that is essential for joining the EU.

Ukraine enjoys special support in Brussels, but it too must heed this message. Without reforms, change will not happen.

Meanwhile, the report confirms rumours that the EU has a new favourite in the enlargement process: Montenegro.

A window of opportunity

The first enlargement of the European Economic Community – the organisation that subsequently became the EU – took place back in 1973. The last EU enlargement was forty years later in 2013, when Croatia joined. Since then, however, the process has stalled. Europe began to talk about "enlargement fatigue".

But 2022 ushered in a new period of history.

The Russian war brought about a radical change of perspective for the leaders of key European states. There is now a consensus within the EU that enlargement is necessary.

It is now a question of security rather than just economics.

This shift in outlook allowed Ukraine and Moldova to obtain candidate status and begin accession talks at record speed. Many within the EU believe that Ukraine’s membership is essential for establishing a lasting peace.

However, this window of opportunity may be short-lived.

During the presentation of the new report, Commissioner Oliver Várhelyi made an ambitious prediction about new EU members joining within the next five years. "The next Commission could be an enlargement Commission," he said.

Yet political will alone is not enough to integrate a new country – especially one as large as Ukraine – into the single market if it does not meet the necessary technical criteria. Otherwise, the single market could collapse.

And Ukraine faces systemic challenges in meeting those criteria.

Ukraine has mixed reviews

"Progress over the reporting period from September 2023 to September 2024 has not been as significant as we’d hoped," Oliver Várhelyi acknowledged. This applies to the other candidate countries as well as Ukraine, as all have shown stagnation in their integration metrics over the last year.

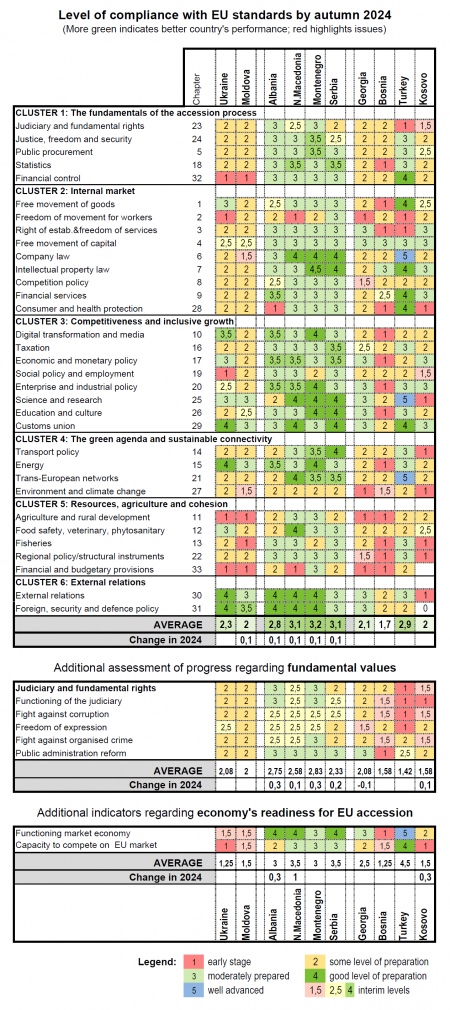

European Pravda presents a comparative analysis of the countries in the Enlargement Package, following the same methodology as last year.

We have categorised some countries as a "problematic" group that shows minimal commitment to EU integration: Georgia, Türkiye (negotiations frozen since 2018), Bosnia (which has not met the conditions to start negotiations) and Kosovo (only a "potential candidate").

Six other countries are advancing toward EU membership, though at varying speeds.

Of these, Ukraine is the only one that has made no substantial progress in alignment over the past year.

The progress made by the remaining five states has been modest, but it’s progress nonetheless. Várhelyi is correct in saying that all the candidates need to speed up their efforts.

At the current pace, with 0.1 points of progress made annually, preparation for membership would take decades.

What else does the European Commission’s data reveal?

It shows that Ukraine is not a frontrunner among the candidate states. Setting aside the "problematic" group, Ukraine ranks only above Moldova. Having started with the lowest baseline in 2022, Ukraine has been moving faster than the others, but it remains the furthest from EU accession.

Another notable aspect is that Ukraine is a country of contrasts.

It has both the highest and the lowest scores depending on the area being evaluated. For five of the 33 negotiation chapters,

Ukraine has the lowest possible score,

indicating that these areas have barely started to align with EU law. But there are four other chapters where Ukraine has achieved a good level. No other genuine candidate, including Moldova, has a more contradictory profile.

This disparity is risky.

Many economic reforms need time to be implemented. Postponing certain areas "until later" will hinder Ukraine’s readiness for EU membership. Moreover, such uneven progress affects Europeans’ confidence about whether Ukraine is truly committed to joining the EU.

Brussels is wary of cherry-picking, where a partner state selects the most advantageous obligations rather than implementing the whole package.

Speed matters

Among the countries moving towards EU membership, one has emerged as a clear favourite: Montenegro. Despite being led by a complicated pro-Serbian coalition, Montenegro’s government continues to push for reform.

The EU particularly values the fact that Montenegro does far less cherry-picking than any other candidate. They have no 1s in their scores and only four 2s (meaning "some alignment with EU law" in European Commission terms). Montenegro is also the highest-scoring candidate in terms of core EU values (Fundamentals) and has made strong progress with reforms over the past year.

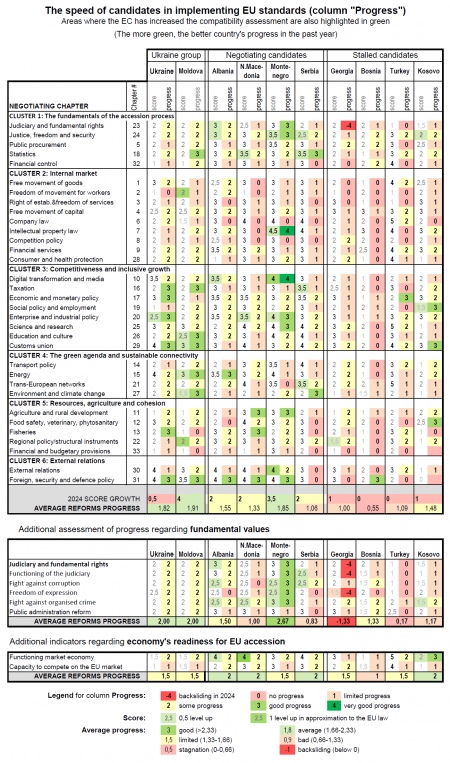

The candidate countries' progress is illustrated in our next comparative table, which shows both the scores achieved (in the left-hand column for each country) and the number of reforms implemented over the past year (the right-hand colour-coded column).

The general conclusion is that the situation is difficult – and not just for Ukraine.

To be frank, the pace of reform across all the candidate countries is either stagnant or very slow.

But Ukraine is in a unique position.

The EU recognises that Ukraine has undertaken more reforms over the past year than other candidates have, with only Moldova and Montenegro slightly ahead. Yet, paradoxically, these reforms have not altered Ukraine’s readiness for EU accession.

With "good progress" (as the EU phrases it) in six areas, Ukraine has only managed to raise its score by a paltry half-point in one of them.

One possible explanation that has been suggested by both the Ukrainian government and the European Commission is that last year Kyiv focused not on adapting to EU standards, but on implementing the reforms required by the Ukraine Facility and pre-accession screening. Actions were taken, but there was minimal change in terms of alignment with EU law.

But this explanation does not change the main takeaway: without radical acceleration of accession-related reforms, Ukraine will not succeed on its path to the EU.

The Ukrainian government must grasp this as soon as possible.

It isn’t just Ukraine: the truth is that reform is too slow across the board. Even Moldova’s score of 1.91 out of 4 is insufficient for membership, be it in 5 or even 15 years.

However, the fact that other candidates are also making slow progress is no excuse for Ukraine. Every candidate’s progress depends on its own efforts, and Ukraine must now aim to lead, not necessarily in our alignment scores, but at least in the pace of reform.

Sergiy Sydorenko

Editor, European Pravda

Translated by Daria Meshcheriakova